The Scotch Snap goes to Poland

My recent discovery that one of the interpolations in Coppélia for Franz’s variation is from a “Scottish” ballet (Gretna Green, by Guiraud) encouraged me to re-watch Philip Tagg’s wonderful hour-and-a-quarter long documentary on the so-called Scotch snap. I say “so-called” because that’s the chief take-home point of the documentary: it’s called the Scotch snap, but it was once as characteristic of English music as Scottish, and the speech rhythm from which it derives is still prevalent in English today. If there’s a reason why we think of it as Scottish, or “Celtic” it’s because the English musical tradition where it was once common has been wiped clean, “upgraded” as Tagg puts it, of such elements, precisely because they became associated with lower class, country people. I suppose you could compare it to the way that people with regional accents or sociolects are taught RP in elocution lessons. English music from roughly Handel onwards became the Elisa Doolittle or Lina Lamont (see below—and for more on all this, watch Tagg’s video).

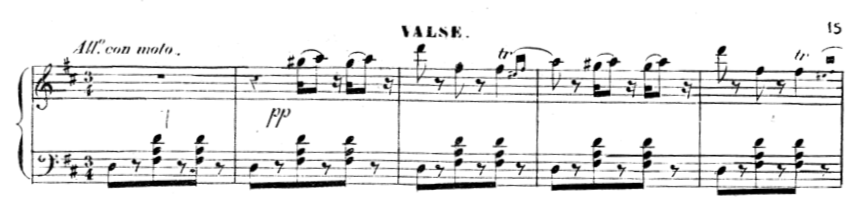

In the Guiraud solo, that snap is an an identifier for “kind of Polish/Ukrainian” (i.e. 19th century Galicia), except that in the piece it came from, Gretna Green, the snap is Scottish. There is also the drone D in the bass that suggests rusticity, but it’s the snap that’s the real giveaway. Here are the two side by side:

As Tagg argues in his video, what this is about, surely, is not so much race, nation or ethnicity. but class. The same seems to be true of Coppélia: it doesn’t really matter (at least to modern audiences, I suspect it did matter to Delibes) where Franz comes from, what matters is that he’s a rustic local, not a prince, or an urban(e) shopkeeper or toymaker. In theory, Franz could be dancing to Chopin, since Chopin was Polish. But how wrong would that have looked? Chopin is the wrong class of Pole, the concert-giving, salon-performer in Paris, the poet with a floppy cravate in Les Sylphides. Franz is a rustic, like those villagers in Giselle whose waltz is all Bohemian snaps.

But I’m leaving out an important detail here. The music that Delibes *cough* “borrowed” the “Friends” tune from, is an art song by Moniuszko (see earlier post for all the details), and the “snap” doesn’t exist in the original: it’s something Delibes added. The notes at the same position in Moniuszko’s song are semiquavers, and they are for a single syllable.

Fair enough, there’s an acciaccatura in the piano accompaniment but does that amount to a Scotch snap? Not really, I think.

They would have…

I can guess how that Gretna Green solo ended up in Coppélia. It sounds kind of foreign, kind of rustic. That’s usually enough geographical detail and social context for the average ballet scenario. I once heard a student ballet teacher tell a class of children, “Your hands are like this in this dance, because they would have…” That phrase, they would have has stuck with me ever since: she was talking about character/national dance, referring to people from another country as if they were not only remote geographically, but also historically. There was no detail about who “they” were, or where they were from, they were just “they.” The construction would have seemed to imply that what these people did (whoever, or wherever they were) could not be documented in terms of real people or events, but just as a list of possibilities, of permanent characteristics. That sums up the strange universe of ballet pretty well. We do this, they would have done that. I’m not sure what it was that the hands were supposed to be doing. Digging potatoes? Showing off handkerchiefs that they had embroidered? It’s not the students’ fault: this is the casual, institutional racism, snobbery and ethnic nationalism of ballet that seeps from the walls of the art form.

Rustics and rustication

Ballet apparently needs settings like these to make it interesting, to give it what programme writers call “colour.” Here’s an example from Pittsburgh Ballet, which is so representative of the genre, that you should not read anything into the fact that it’s that company or that author. It could be any ballet programme, anywhere:

Nuitter and Saint-Léon changed the names of the characters, except for Dr. Coppelius, and moved the location from Hoffmann’s Germany to Galicia, a province of Austria-Hungary, because it was thought to be more colorful. Today’s map finds Galicia in southeastern Poland and western Ukraine. The “color” of the region can be seen in the brilliant colors, heavy embroidery and elaborate trimmings of the peasant costumes, widely enhancing the designer’s palette, both then and now. It can also be heard in the rich nationalistic melodies and complex folk dances of the composer. (Source: Pittsburgh Ballet Programme Notes)

Before continuing, let’s take a moment to remember that “Friends” is not by Delibes, and nor is the Csárdás, and nor is this variation for Franz. I’m not sure what a “rich nationalistic melody” sounds like, or that Delibes “folk dances” are really that complex, but never mind. The main point is that ballet seems to need those Scotch snaps (or Celtic, Hungarian, Polish, Galician, Bohemian or whatever kind of snaps they are) to prevent the music from being a wall of ballet gammon, or perhaps ballet mayonnaise. It’s a perverse form of “poverty tourism” where you can admire the rustics from the comfort of your box in the theatre, but at the same time shine a light on your own dullness, your lack of the rhythmic vitality demonstrated by the people on stage.

No-one, particularly not your average ballet audience, would actually want to go to those places of course. One of the punishment for academic misdemeanours at Durham University was (and still is) “rustication,” i.e. being sent back to the sticks. According to a lecture by Dr Martin Pollack, this is apparently how Austrians (who annexed it in the 18th century) once viewed Galicia, a place you didn’t want to get sent (one writer referred to it as “Halbasien,” “half-Asia”), at least, until the job of Germanification had been completed, and the locals had been tamed.

Of course, there is poverty, and there is staged poverty. Pollack mentions that his stepfather had been stationed in Galicia in the first world war (so less than 50 years after the premiere of Coppélia). His memory of those experiences included “wide wooded uplands, and impoverished hamlets where everything was built from wood, even the churches.” The wooden churches were what surprised his stepfather most, since in his native Austria, he had never seen such a thing. One thing is for sure: it didn’t look like the set of Coppélia.

The inhabitants of Galicia aren’t just a fictional people invented for the ballet scenario. They had names, and lived and died in villages with names. Where he can, using archival records, Tagg names some of the English workers who went as indentured labourers to the US in appalling conditions. Likewise, you can find out about the inhabitants of Galicia: Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, and others at the time of Coppélia by searching the All Galicia Database which has records going back to the 18th century. Obviously, Coppélia is a fiction, not an attempt to portray real people. But it matters that Galicia is a real place, with complex histories, if you’re going to start saying local colour, and they would have…

Esmeralda and the Truands

Next on my list is La Truandaise from Esmeralda, another example of the “Scotch” snap being used to denote otherness that is geographically vague (Bohemian? Gypsy?) but definitely poor. In the video below (assuming YouTube don’t block it) of Osipova dancing the “Truandaise,” the flexed foot is perhaps the movement equivalent of the Scotch snap. She does it, because (as a ballet teacher might say) they would have flexed their feet (because they couldn’t afford to go to ballet classes, and find out about good toes and naughty toes). So how could she afford pointe shoes then? Best not to ask too many questions.

Feed the birds

Tagg demonstrates through many examples that the Scotch snap rhythm is common enough in English speech that it is bizarre that it should have come to denote anyone from the British Isles except the English (as “Celtic” has come to mean). Playing for class today, I discovered another example: “Feed the Birds” from Mary Poppins. Tup-pence, Tup-pence. I “discovered it” because as I was playing it, I thought first of all, “here’s a rather odd example of a “Bohemian” snap in a musical, until I realised that is not Bohemian at all, but English—and, fitting Tagg’s hypothesis, it’s a certain kind of Englishness—an old beggarwoman selling breadcrumbs for tuppence a bag. If you’d never seen Mary Poppins, and just heard the tune of Feed the birds, you might well think that it’s a tragic song from old Bohemia.

Feed the birds is an interesting case. According to the Wikipedia page on the song, the author of Mary Poppins, Pamela Travers, only wanted period Edwardian songs in the film, and had to be coaxed round to Americans writing the soundtrack. Oddly, it turned out to be an excellent choice, because the Sherman brothers portrayed Englishness in music particularly well with those “Scotch” snaps (there’s another one in A spoonful of sugar. The class issue is less clear there, though Mary is still only the nanny, however posh she might be). Listening back to “Feed the birds” with Tagg’s documentary in mind, I wonder what it is that I think I can hear—and it’s the very ordinary speech of my childhood. My dad, and the local shopkeepers saying “tuppence” or “tuppence ha’penny,” or “throppence.” The (musical) idea that the Scotch snap is Bohemian, gallic, celtic, Hungarian, or whatever, has blinded me to the rhythms of my own speech. Extraordinary.

What a difference a demisemiquaver makes. And how much history you can write, just by focusing, as Tagg does, on detail like this. And as one final aside, writing this post I came to hear of a novel I should have known about years ago, Joseph Roth’s, Radetzky March (Dr Pollack mentions it in his lecture), and am thoroughly enjoying reading it. I wish I had read it before any of my travels in what was once the Austro-Hungary, and I suspect it will make great background reading for Coppélia.

Update: House of the Rising Sun, another candidate

Playing this for class the other day, I suddenly realised that the “scotch” snap features in this song, too: and it’s nothing to do with the words this time, because no-one pronounces New Orleans with the emphasis on the new (not even The Animals, later in the song), though many a poor boy is an example of the “scotch” snap in everyday English.

It’s interesting to compare this with the 1933 recording of the related Rising Sun Blues by Tom Clarence Ashley & Gwen Foster. Ashley said he learned it from his grandfather, and the song—or a variant of it—may date back to the 16th century.