- Download the waltz by Kéler in piano score (free pdf)

- Read more about my Year of Ballet Playing Cards

Elastic or expressive timing is a feature of music in ballet classes that I’m rather nostalgic for. When I meet teachers who still do it, I feel as if I’m back home again. Recently, I’ve found that I need a particular category of waltz for company classes with multiple pirouettes, where the tempo needs to be forgiving, accommodating, like stretch fabric jeans that can be a couple of sizes larger than the label suggests. Schmaltzy is what we would have called it a few decades ago, but it’s a long time since I heard that word.

How I learned to love the schmaltzy waltz again

When I first started working in ballet, I’d be slightly appalled if a teacher wanted part of an exercise slower than the beginning, to make space for a different kind of step or more pirouettes. Now I enjoy the interaction with the teacher, enjoy the challenge to get the tempo change right and still make it sound musical.

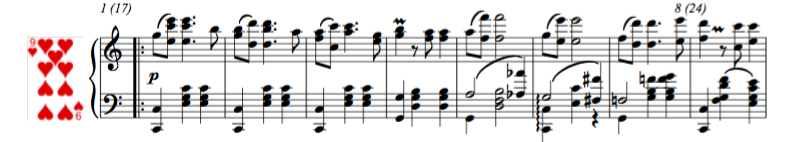

You can’t do this with any old waltz, and particularly not with the kind that has an overwhelming metrical level, rather than switching between several through the course of the tune. I’ve put Deutsches Gemüthsleben in the “hearts” section because it has places where it’s in six (see various posts on triple meter), but the opening is very definitely in three. Sections E and F do what the Swan Lake Act 1 waltz does, which is to drive the accent to the second bar and fourth bars. At the ends of sections, the three-in-a-bar is suddenly more marked. In other words, what appears to be simply “3/4” has several different kinds of metre both internally (within a single phrase) and from section to section.

I’d never heard of Kéler until I read that he was the source of the Hungarian dance that made Brahms famous when he plagiarized it in its entirety, believing it to be a folk tune (like folk tunes just precipitate in the ether like ectoplasm, huh?), but I’m glad I found him. See more in Nancy Handrigan’s wonderful thesis On the Hungarian in Brahms, especially pages 55-56, and for the proof, listen to the original Kéler below (scroll to 2:56″ if it doesn’t start there automatically).

I haven’t found a performance of this Deutsches Gemüthsleben Walzer that I like, or that does justice to its potential for elastic timing (some of which Kéler writes into the score), but it’s remarkably similar to the waltz in Der Rosenkavalier, which is the feel I’m looking for (see below – scroll to 5:40 if the technology doesn’t make it start there automatically).

It might also not escape your notice that both Kéler’s melody and Richard Strauss’s have a lot in common with The Lonely Goatherd from The Sound of Music, and also — i noticed much longer aftewards — with the “Waltz of the Flowers” from The Nutcracker. Perhaps these falling thirds against an unchanging major floor is music’s answer to Gemüt, and perhaps Gemütlichkeit is the best way to describe character of the schmaltzy waltz that you need for a certain kind of pirouette: music that’s warm, roomy, comfortable, supple, supportive, like an armchair by the fire in an old pub.