On the weekend, I was playing the tarantella-ish Prince’s solo from Sleeping Beauty. Then, as every time I play this music, I panicked half way through the introduction – how many duh-da-da’s have I played? How many should there be? Is it 5? 3? 6? 4? Getting it wrong is enough to completely floor the poor person doing the solo. I know in my heart that it’s really just ‘four in’ with a two quaver anacrusis, but if I look at the score and try to play it like a ‘proper’ 6/8, I flounder.

But now that I’ve read those the two articles on metre in 18th century music by Danuta Mirka and William Rothstein that I mentioned in my last post, my panic is over. I don’t try to inflect the solo with the metric rules I learned at school (i.e. it’s in 6/8, so therefore the upbeat must be light), and I just play it as if it was in 3/8, or in 6/8 but starting on the half bar. I don’t try to convey the duple metre of the 6/8 bar, or try to make the ‘2’ of the first bar lighter than the 1 that I haven’t played because there’s a rest there (!)

Although Rothstein and Mirka are writing about 18th century music, I think the theories work for this, and for a lot of Tchaikovsky, particularly when it comes to the French songs in Nutcracker (like Cadet Rousselle or Bon Voyage Cher Dumollet and others). Not surprisingly, they comply with the ‘French compound metre rule.

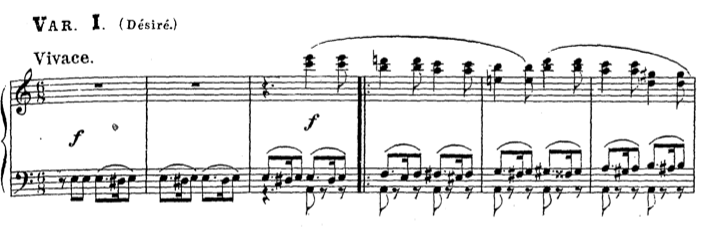

This Desiré solo is an odd case, somewhere between an Italian and a French conception of 6/8 in Rothstein’s terms.

- It’s Italian (Rothstein) or compound 6/8 (Mirka), because each bar is a compound of two 3/8 bars, not a ‘duple compound’ metre in the modern sense. It could easily be written in 3/8, because it’s not that duple at a higher level.

- At the same time, it seems to lean towards a French compound metre in Rothstein’s terms, because it has a half-bar anacrusis, and the cadence (i.e. when it resolves to a root position chord at the end of a phrase), is on the first beat of the bar.

I think it’s more of (2) than (1), and it helps when playing it is to think less about the notated metre and the metrical accent it implies, and more about the way the melody is aiming towards the final cadence, like one of those end-accented Italian words in a line from an operatic aria (e.g. “Fortunatissimo per verità!” from “Largo al factotum” from The Barber of Seville).

So why not write it in 6/8 but displaced by half a bar? Because of (2) above – it must resolve on the downbeat according to the ‘French compound’ rule. Why not write it in 3/8? Because the composed metre alternates between simple and compound versions of 6/8 (in Mirka’s terms), and Tchaikovsky needs the larger-sized bar for when he wants a duple metre feel. When he shrinks the melody into double time, you can’t bar it any other way without it looking weird.

So Rothstein’s thoughts on national metrical types and Mirka’s discussion of ‘composed metre’ versus ‘notated metre’ make for an interesting two-pronged analysis of this piece that has annoyed and intrigued me for so long. For example, the bars with the semiquaver flourishes over the Neapolitan sixths near the end turn the composed metre into 4/4, and then immediately after, the cadential bars turn it into what you could consider a series of 1/4 bars – since you get a repeated half-bar figure that resolves every half bar (of the notated metre), a diminution by a factor of 4.

As for what’s going on in the middle section, Lord only knows. The resolutions now come in the middle of the bar, so what’s happened? It’s not in some kind of composed 3/8, because the cross-rhythms make for a longer composed/perceived metre – one way of looking at it is to see the final bar of the previous section being in 9/8, followed by two bars of 12/8. But not for long. Or maybe the first section is effectively in 3/8, the second effectively in 6/8 with the ‘real’ barline halfway through the bar. But what happens between that and the tune coming in again, it’s a bit of metrical mess, with Tchaikovsky just vamping garrulously between two chords (nothing new there) till he’s ready.

Is it clever? I’m not sure. All these metrical shennanigans make the piece awkward to play, and difficult to regulate in terms of tempo, and – for heaven’s sake – it’s only a 45 second solo, how much more detail do you want to cram in? But thinking about the music in terms of composed metre rather than notated metre, and as a ‘French’ or ‘Italian’ 6/8 rather than what we now call ‘compound duple’ time, makes playing it easier: you’re not trying to force a compound metre onto musical material that is doing something else.

Update on 6th August 2015

I’ve revised my opinion on this: Rothstein is absolutely right, but I am wrong here – what I find difficult is precisely the point of the music, the interplay between the vocal phrase and the notated meter. It is as if there is in fact a continual cross-phrasing at work. I had tried to simplify it for myself by trying to underplay the metrical accents, but in fact, I think what is required is to aim to be able to play both lines with their metrical implications against each other. I’ve managed it a few times in class with this piece, and noticed that ballet exercises often do the same: they’re “cross-phrased” against the music, but without the same kind of metrical accent as the accompaniment: there are fewer metrical implications. That probably isn’t very clear, but what I’m saying is, with music like this, there isn’t an easy way – you have to suck up the implications and try to do it, I think.

References

Mirka, D. 2008 Metre, phrase structure and manipulations of musical beginnings In D. Mirka & K. Agawu (eds.) Communication in eighteenth-century music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 83–111.

Rothstein, W. 2008 National metrical types in music of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries In D. Mirka & K. Agawu (eds.) Communication in eighteenth-century music. Cambridge UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 112–159.