For ballet music nerds like me, this is quite the event in our tiny corner of the musical universe. Ryan Hirst has uploaded to IMSLP a beautifully typeset edition of the two-violin répétiteur score held in the Sergeyev collection at Harvard.

When I say “beautifully,” let me count the ways:

- It looks lovely on the page. It’s been done in MuseScore, which is free, but it looks aesthetically nicer than any score I’ve ever produced in Sibelius, which cost me around £650 for the first hit years ago, and then nearly £100 per year to keep it updated. Bloat doesn’t even begin to describe it, but when everything you’ve edited for 20 years is in Sibelius, you don’t want to move. Making stuff look good on the page is a human skill, the software won’t do it for you, so hats off to Ryan for this achievement.

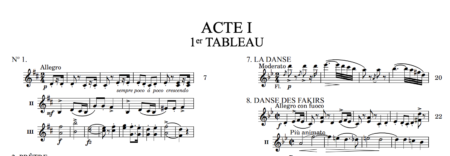

- It’s got a thematic index. This is so rare in ballet that I can remember precisely which few scores have one. I’ve probably spent several hours if not days of my life going through ballet scores trying to find things that someone has requested for a variation class, a job that’s simplified no end if there’s an incipit index like this. Not only can you quickly identify themes and find the relevant page number, you also get a bird’s-eye view of the structure of the score. The index also gives incipits of sub-sections within a particular number. This helps even more, since in my experience, a lot of teachers’ favourite bits for class are hidden within a larger section. This score is worth it for the index alone; in a online world full of AI slop and videos that take 10 minutes to tell you how to do something that could have been reduced to three bullet points, this concise map of the ballet is music to my eyes.

- It’s got running footers telling you which act/tableau you’re in.

- It’s got footnotes indicating dubious notes or markings.

- Interpolations are credited to their original sources.

- It’s laid out as far as possible to suit dance musicians, i.e. to favour eight count/bar phrases.

- There are editor’s notes at the beginning, giving full attribution of the sources.

- Unlike some other editions of ballet scores that put a heavy price tag on what is essentially public domain material in a costly wrapper, this is a transparently public domain, share-alike product. It makes me sad and angry at the same time that before long, someone will upload this to Scribd (as people have of my share-alike stuff) and cause others to pay a subscription to Scribd for something that was a labour of love, but that’s where we are.

Répétiteurs were used for ballet rehearsals until late in the 19th century (see an earlier post on violins and pianos in ballet). Given the predominantly melody-and-accompaniment style of these scores, two violins can make a pretty good job of representing “the music” in rehearsal, and the répétiteur itself is like a detailed busker’s book or lead sheet. For that reason, this Bayadère score will be very handy for pianists who can fill out the detail for themselves at the keyboard—it’s concise, and easy to read. For violinists interested in the répétiteur tradition, this is most probably one of the first books to approach anything like a published critical edition. Teachers who play the violin themselves, or know someone who can, could construct an entire class using this book.

It’s always surprised me critical editions of ballet scores are virtually non-existent. Given how prone the field is to confusions, ambiguities and interpolations, critical editions are arguably a necessity, not just a pastime for someone with an academic interest. Now that a version of just about any ballet is available on YouTube, increasingly what people do when they want to refer to something reliably is to send a link to a particular version on YouTube (“can you point at it? Is it on the trolley?” comes to mind).

And who can blame them? Even something as bread-and-butter for ballet as the Black Swan variation or Siegfried’s solo in the same pas de deux is pretty unfindable unless you happen to have worked in the ballet world long enough to know where to find it. That’s not to say that behind the scenes, orchestral librarians at ballet companies spend a lot of time discussing the details, so that in effect, what companies end up with privately are a form of critical edition. But the critical part is largely hidden from view, and the scores are not published. Although there are many different versions of La Bayadère around, being able to quickly and clearly access a source like this makes comparing them a hundred times easier.