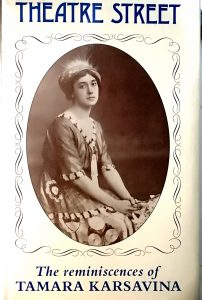

It’s not often that books on ballet say much about music in class—in fact, outsiders often seem to have more to say about it than the teachers or dancers themselves. But Tamara Karsavina’s memoirs Theatre Street have several lovely glimpses of the sound world of her classes and life in the theatre. I saved all these up for my own future reference, but I thought it would make a rather nice post, too.

Lessons with “Aunt” Vera Zhukova, 1893

Karsavina’s father didn’t want her to become a dancer—he’d had too much experience of the shennanigans, skullduggery and precarity of life as a dancer himself at the Imperial Theatre to wish the same on her. Mummy had other ideas, so she secretly sent Tamara for lessons with a family friend, Vera Zhukova to see if she had any aptitude. In a scene that will resonate with dancers currently in lock-down, Zhukova prepared the a make-shift studio at home by clearing one end of the dining room, and fixing a removable barre on hinges across the door. “Music” came from a stick:

Aunt Vera put on carpet slippers and had a small stick to beat time. For the first two months she kept me to bar practice; and only when my feet were turned out properly did she begin to give me some exercises in the centre”

Karsavina’s father’s violin repertoire for class

Eventually, daddy found out, and agreed to teach Tamara, in the evenings after work, playing his violin as accompaniment. For those interested in the tunes-versus-improvisation for class question, here’s one piece of the jigsaw:

He played a great variety of tunes for my exercises, bits of ballet music, bits of Faust and Lucia di Lammermoor, occasionally singing the words. His favourite was a Jewish polka. The one for which I often asked was the Marseillaise. The grand battement was not half so exhausting when done to its brave tune.”

Violins, pianos, and player pianos

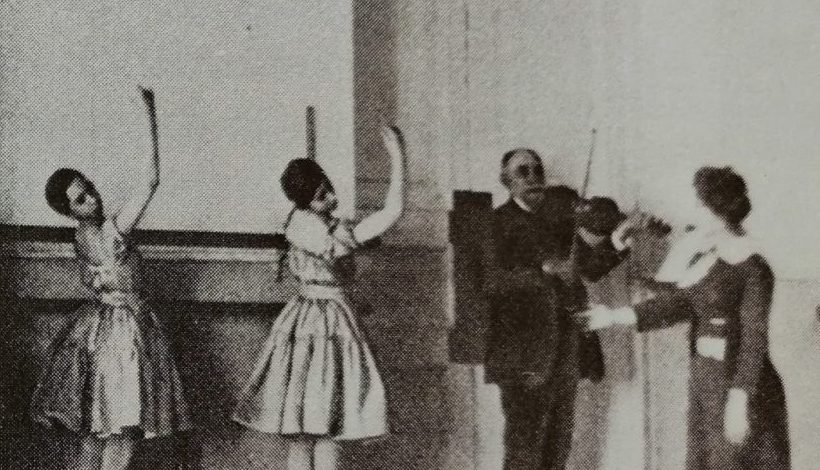

On page 67 (of my edition of the book) there’s a picture of a class at the Imperial School, showing a violinist standing at the head of the barre, in the doorway. I assumed at first that the woman diagonally facing the barre dancers was the teacher, but she may not be. Unless the picture was just added randomly to the book, this presumably must be somewhere in the late 1890s, as Karsavina herself graduated in 1902. It raises an interesting question about the changeover from violin to piano at the Imperial Theatres schools at the end of the nineteenth century. It grew into such a large paragraph that I created a new post on that topic altogether, Pianos and Violins in the Ballet Class.

Rehearsing sotto voce

There’s a lovely reference to the term sotto voce that’s obviously familiar to musicians, but which I’ve never heard used in relation to dancing—I guess she means “marking at the back,” so to speak.

“Prima ballerinas never spared themselves when rehearsing at the Maryinsky, though going through parts sotto voce, as it was oddly called, was not infrequent when rehearsals were held at the school.”

On page 82, there’s another photograph of a ballet master with violin bow (but no sign of the violin, unless it’s a pochette, and thus too small to be seen).

On Christian Johannson’s violin playing for class

To be honest, class with Johannson sounds a bit of a nightmare. Though respected and revered as a teacher, he was old, blind in one eye and never got up to show steps, indicating them instead vaguely with shaky hand movements. He was Swedish by birth, and spoke broken Russian interspersed with French, though seemed to have a rich repertoire of insults, calling Karsavina a “cow on ice” for example. And the music?

Johannsen gave us very intricate steps, very difficult to fit to the music. He laid his fiddle across his knee and played pizzicato, using the bow only to point towards someone faulty, nine times out of ten to me. “I see you. Don’t you imagine I can’t see your bumbling feet.”

Playing duets in the round room

Reading memoirs of dancers from this period sometimes takes you by surprise, when you realize just how musically literate they were:

One morning, another girl and I sat at the piano in the round room. A volume of overtures for four hands in front of us, we struggled through the ‘Matrimonio Segreto,’ when a sound of the opened door made me turn my head. Volkonsky very swiftly walked in, making for the opposite door leading to the dancing rooms. . . . The music on the stand caught his attention. He fixed his eyeglass, ‘Cimarosa, I see; please go on.’ I noticed a slight nervous twitch in his face, and his exquisite hand as he stood [p. 105] by the piano lightly tapping on the lid. ‘It should be taken in a quicker tempo, when you have learned, it he said, and then asked if there were any dancing-classes in progress.”

If you’re a believer in systems of training, and that you only have to follow what someone else did in order to repeat their success, then first learn the piano, find a piano-playing friend, then download what is probably the same duet arrangement of Il Matrimonio Segreto that Karsavina and her fellow student played.

On Nijinsky being that dancer in the class. . .

After seeing a boy jump higher than anyone, she asks who it is:

“Who is this?” I asked Mikhail Obukov, his master. “It is Nijinsky; the little devil never comes down with the music.”

On tour with Yegorushka Kyasht

One of the things that is probably hardest to imagine about some performances of the past, is just how execrably bad the music must have been sometimes—not just the wrong tempo (probably), but just plain badly played too ( on Rite of Spring is worth reading on that topic in regard to what purport to be historical reconstructions). On a provincial tour undertaken with Lydia Kyasht’s brother, Yegorushka, the recruitment of musicians was pretty last-minute:

In a few of the big towns the theatre and the orchestra were good, and the performance went on creditably; when we came ot out-of-the-way little holes of the western district, our shows became precarious. The first fiddle of the Maryinsky came as conductor on our tour. Nothing having been organized beforehand, the valiant soul would go out in the morning to collect musicians; collecting was done by means of canvassing pedestrians in the main street. “Can you play some instrument?” he addressed people at random. Not many of them could, but they often gave information as to where one could find a small band. In this district, where the population was almost entirely Jewish, no wedding festivity would be complete wihout some band. At Kishinev [Chișinău, now in Moldova] there was an especially disastrous performance; the unexpected sounds raised by the band (nervousness was to be taken into account) only faintly resembled the well-known music, and at times silence fell but for the obbligato of the double bass and the voice of the conductor singing loud the melody till the musicians, one by one, picked it up.”

The manifesto

Brian Eno’s concept of scenius seems to sum up Karsavina’s life pretty well. In 1920 she teamed up with people at Saturday suppers at her house, and “conceived an ambitious scheme of uniting English composers and artists to establish periodical seasons of ballet” (Theatre Street, p. 193). They drew up a “manifesto” which was signed by Karsavina herself, the designer Claud Lovat Fraser, Arthur Bliss, Arnold Bax, Eugene Goossens, Lord Berners, Holst, Paul Nash, Albert Rutherston and others (p.193). Can you imagine that party?

It so happened that Arnold Bax would go on to write the music for J. M. Barrie’s 1920 play The Truth About the Russian Dancers in which Karsavina herself starred as a non-speaking role—a Russian ballerina who could only “speak” in dance; Paul Nash designed the set and costumes. It was originally planned for Lopokova, who suddenly disappeared at the last minute, ruining everything. You might think that Barrie would never want to work with dancers again after that, but on it went at the Coliseum, and sold out for a month .

The music is available on Spotify if anyone fancies recreating it:

On notation and musical prompts

It was many years before I realized that when dancers say in rehearsal, “Can I hear it please?” they’re not asking because they need to know how it goes (they know it backwards) but because the music jogs their memory for steps, and enables a mental rehearsal as the music plays. Although it’s very familiar to rehearsal pianists, I don’t think I’ve ever seen it referred to explicitly as here, where Karsavina is discussing Sergeyev and his Stepanov notation—and the dancers’ alternative method:

Still, a favourite method of reviving forgotten parts, and the one used by artists, was that of recalling the dance by memory while the music was being played. “Music prompts,” we used to say. Prompting often came from unexpected quarters. Some on of the older dancers, of the grade we surnamed “Near the Water,” would call out “No! No! That is not the step Brianza did in this part, I remember.” Here she would indicate the forgotten step. A piece of water so often figured in the background of the old type scenery that it gave its name to the back rankers.

This is also only the second time I’ve seen the “near the water” phrase referred to. The first time was in Leo Kersley’s A Dictionary of Ballet Terms, where he explains that the term ballérines près de l’eau was a slang term used for the “oldest and least successful members of the corps de ballet of the Paris Opera in the 19th century,” since in that period, the conventional backcloth often had a fountain painted on it .

On Rubinstein’s music for The Vine

And so we come to the thing that drew me into this vortex in the first place. Rodney Edgecombe refers to Karsavina speaking of the Petipa variations (of the Pugni/Minkus types) that were squared up into 32 or 64 count phrases . I hadn’t realized until then that Karsavina had written so definitively about this practice, which came about partly because some enchaînements would often be choreographed first, the music added later. I checked Edgecombe’s reference, which is to this passage, about Rubinstein’s music for The Vine:

This ballet had been given before, but was soon shelved partly on account of its music, considered too symphonic. The music of Rubinstein certainly differed from the favourite type of ballet music, a string of obvious tunes squared up in 32 or 64 bars to fit an amount of steps considered the limit of a dancer’s endurance. . . By his choice of this piece, Fokine established the first point of his creed:—“Music is not the mere accompaniment of a rhythmic step, but an organic part of a dance; the quality of choreographic inspiration is determined by the quality of the music.

On leaving Legat for Sokolova

It’s nice to read, given that there’s so much emphasis these days on the value of boys learning to dance with male teachers because there’s something only men know about male dancing, that Karsavina had decided there were limits to what men could teach women, too. Once again, you’ll recognize the lock-down teaching environment, and the minimal musical means:

But I had assimilated all that the personality of my master could give me, to the degree of being able to execute vigorous steps usually reserved for men, and it became evident to me that I now needed a woman’s tuition. Madame Sokolova was no longer attached to the theatre school. She held a class of her own, to which Pavlova went daily [in 1909]. . . The small room where we practised allowed no space for a piano My mistress sang, rendering the roulades and fiorituri of the old music with admirable clearness.

On Cecchetti’s cane

For those who are really keen to replicate the Cecchetti method with a balletic form of Historically Informed Practice, here you go. When he lost his rag with a student, he’d hurl his famous cane at them: “. . . the same cane blandly beat measure to a softly whistled tune—he used no other music at his lessons.” (Theatre Street, p. 281).

Ravel helps Karsavina count

I’ve never thought Daphnis and Chloë sounded very danceable, nice as it is. Seems Karsavina had issues with it too, but fortunately, Ravel was there to help out:

There were many stumbling blocks in the music of Daphnis and Chloe. In sonority suave, noble and clear as a crystal spring, it had some nasty pitfalls for the interpreter. There was a dance in it for me in which the bars followed a capricious cadence of ever-changing rhythm. Fokine was too maddened, working against time, to give me much attention; on the morning of the performance the last act was not yet brought to an end. Ravel and I at the back of the stage went through—1 2 3 — 1 2 3 4 5— 1 2, till finally I could dismiss mathematics and follow the pattern of the music.

On de Falla

I have to declare an interest here. One of the first things I did when I went to the RAD in 1999 was to empty out the massive music cupboard in the music room, and catalogue everything in it. In the process, I found quite a few treasures, including a piano reduction of The Three Cornered Hat that had a handwritten message to Karsavina on it, from de Falla, saying something like “So sorry to miss your first performance, hope to see you soon.” I couldn’t believe my eyes. In the bloody cupboard of the music department. Rest assured, it’s now safely in the library in a safe. And here’s some background to that story:

De Falla, great musician, gentle and unassuming, reminiscent of an El Greco portrait, did not think it derogatory to play at our rehearsals. A magnificent pianist, he had delighted Rouché, director of the Paris Opera, with his rendering of the score of the Three-Cornered Hat. On another occasion, he had played for me alone the score of his ballet, L’Amor Brujo.

References

So enjoyable and impressive, thank you!