Since the lock-down/Covid-19 pandemic, I have had five or six complicated queries from colleagues (musicians and ballet teachers) because they think I know something about copyright. The thorniest issue is that of cover songs on ballet albums. Unfortunately, just as there were many lawyers who said they weren’t going to be drawn on planning law in relation to Dominic Cummings’ cottage on his parents’ estate because it’s just too complex, the only thing I know about music and copyright is that it’s a minefield, and that the whole nature of licensing and the music business and distribution platforms and formats is changing so fast, that whatever you knew last year probably doesn’t fit 2020 .

What follows below started off as an email to the few colleagues who’ve asked me questions recently, but it got too long, and went into areas that may not interest them. I thought that if I posted it here, there’s a chance I might get some responses from others with advice, experiences, insights, corrections, or further questions, so here it is. Please add questions/comments using the comments box below the post.

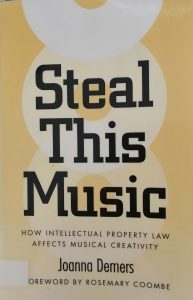

Joanna Demers covers cover songs

On the back of my last post, I ordered Joanna Demers’ book Steal This Music: How intellectual property law affects musical creativity . It’s mainly based on US law and cases, but I think a lot of the principles are international. I’m fairly certain that she’s solved the question I’ve been asking myself for years, as to whether the kind of arranging that you do for ballet class albums constitutes a derivative work, and hence an infringement if you don’t apply for permission to the publisher. This is the kind of backroom conversation that my colleagues and I have had for years: you wonder whether cutting a couple of beats of the end of a phrase to make it square for ballet, or turning something from three into two or vice versa, constitutes more than a cover version. That’s the problem for us—we work in this weird corner of the musical world where we don’t exactly want to cover a song, we want to get a cookie cutter and make identical biscuits out of the phrases. I have applied for permission in the past, but as time went on, I simply became very cautious about what I did with songs, and whose songs I did it with, and just paid for the MCPS licenses.

From what Demers says (there’s a whole chapter on arrangement) the nature of the Compulsory Mechanical License (i.e. the obligation of the publisher to enable you automatically to cover a song through a collecting society such as the MCPS provided it has already been recorded once) is that it allows you to make an arrangement of the song, though without changing the lyrics, or substantially changing the melody. The wording of the US 1976 copyright act is that a compulsory licence (the compulsion being on the side of the publishers to grant it, remember, for the requisite fee) entails “the privilege of making a musical arrangement of the work to the extent necessary to conform it to the style or manner of interpretation of the performance involved.” (Demers, 2006, p. 39)

“Remarkably,” Demers continues, the compulsory license for music allows for both considerable similarities and considerable differences between an original and a recorded arrangement. . . Courts have traditionally interpreted this clause liberally to allow for substantial disparities between an original and its arrangements” (Demers, 2006, p. 40).

The only reason that you would need to apply to the publishers would be if you intended to change the lyrics, or change the melody so much that it’s unrecognizable, wanted to publish the arrangement in notation, and/or claim a proportion of royalties for the originality contained in your work—i.e. if you wanted to actually argue with them that it was a derivative work, rather than a cover version. The chances of you convincing a publisher to give you a percentage are pretty slim, if not non-existent. This, Demers says, is why so many arrangers looked to the classical/public domain works to make arrangements from—all the albums that jazz players made of jazz standards resulted in no song royalties for the performers.

I have no idea, but I’m guessing that there may have been a fruitful negotation between Joby Talbot and the White Stripes when he arranged their songs for Wayne McGregor’s Chroma. But for you and me making a mazurka out of a Madonna song for a ballet album, I don’t think the publisher would answer the phone, let alone consider giving us a proportion of the royalties. I’m interested to know how easily EasySongLicensing could get a print licence for such an arrangment. They promise access, for a fee, to their “‘little black book’ of protected industry contacts” and in my experience, that’s often the only way you’ll ever get a music publisher to pick up the phone, unless they forgot to disconnect it.

The upshot of all that I don’t think any ballet pianist needs to worry about infringing copyright as long as they obtain the MCPS licence and credit the original songwriters. I even suspect that some of the people that I’ve spoken to in the past at publishers have themselves been hazy about the difference between arrangement that needs permission, and one that can be considered a cover under the terms of compulsory licence. One delightful VP of an American publishing company, when I was fretting about having put a dominant-tonic ending onto a song that in real life faded out, said initially that she couldn’t see it as a problem. But a moment later she said, “though, actually, he [the composer] can be quite fussy sometimes. I’m not sure, to be honest.” The problem here was that this was during my RAD days, so we were also publishing the sheet music. For sheet music, the arrangement does have to be agreed by the publisher, with the relevant copyright notices etc.

D’Almaine v Boosey: Hooked on classics c. 1835

One of the earliest copyright cases that might have some bearing on ballet albums (D’Almaine v Boosey [1835]) involved Musard’s creation of quadrilles and waltzes based on on themes from Auber’s opera, Lestocq . It’s a different kind of case, in that here, the defendant had made the arrangements without the permission of the publisher, and was trying to claim that making tunes suitable for dancing needed considerable skill, and thus what he’d done did not constitute piracy (i.e. he could sell the dances as his own work). The plaintiff’s experts argued that any variation in the melody was a constraint of the quadrille or waltz form, and not down to creative originality. The judge found for the plaintiff, noting that any layperson could easily recognize the original melody: adapting it for a dance made no difference to the original subject. Moreover—ballet pianists take note!—whereas it took a genius to construct the original melody, “a mere mechanic in music can make the adaptation or accompaniment” [d’Almaine [1835, p.123, cited in Barron 2006, p. 121). As Jane Ginsburg adds, commenting on the same case: “If the second author is a genius-free mechanic, in other words, if he is not really an author, then he can be an infringer” .

In the end, although I’m sure that a case from 1835 is not going to have much bearing on a ballet album made in 2020, this seems to offer a reasonable answer if you’re asking yourself whether what you’ve done constitutes a cover that doesn’t stray too far from the original. If it’s so far from the original that a layperson couldn’t tell that it was the same tune, then you’ve overshot. But then, what would be the point of doing that anyway, if no-one would recognize it?

Cover songs on ballet albums in the age of the YouTube ballet class

I’ve gone down this particular rabbit hole because a dance teacher recently rang me up saying that she wanted to use some recordings on her YouTube channel, and wasn’t sure whether she was entitled to or not, or how—if she used music from a ballet class album—the pianist or copyright owners of any covered songs would be recompensed.

If you want a similar case, I think you would have to look to Joe Wicks’ PE classes, which, despite being incredibly popular, didn’t use music due to copyright restrictions—until George Ezra piped up and said, hey, use mine! The reporting here is a bit hazy, because it says that Ezra has “become the first to allow Wicks the use of his material for free.” It’s hard for me to imagine what the process is behind the this, and how many people apart from Ezra had to be involved in the agreement. A friend has pointed out, however, that the undocumented issue in the press reports of this feelgood story is that as soon as you use copyrighted music in a YouTube video, the copyright owners automatically get 100% of monetization. In Joe Wicks’ case, he was donating his income from the channel to the NHS, so presumably the problem was not so much in obtaining or clearing music for the channel, but preventing the income from being diverted to songwriters. That will also be a problem, presumably, for the teacher who wants to make money out of their classes: Content ID should fix the issue of using copyrighted music, but it will effectively stop the teacher from making money themselves. Presumably, a kind-hearted pianist could offer a royalty split to the teacher after the fact, but it would have to be a private arrangement, not a question of button-clicking yet.

Whatever the background process, as far as musicians are concerned (i.e. ballet pianists, in this case) it seems to me there cannot be any hope for anyone being recompensed if performers don’t obtain the relevant licenses when they release albums—and by that, I mean registering their own work as much as obtaining licences to perform anyone else’s. What’s more, with regard to cover songs, it appears that the compulsory licence is not applicable in retrospect if you went ahead and released cover songs without getting a licence in advance. In other words, if you release an album without getting your MCPS licence, you can’t apply in retrospect, without, I guess, trouble or money changing hands.

Another awkward question: what about moral rights? It’s a pretty unlikely scenario, but stay with me for the sake of the principle—a pianist makes a cover of Tiny Dancer, which Elton John has not authorized Donald Trump to use in a campaign, and then a pro-Trump ballet teacher does a class in a MAGA hat and a stars-and-stripes leotard, using the pianist’s cover version, and uploads it to YouTube. I have no idea what happens then, or which organization or individual is responsible for what, and what action, if any, any of them would be in a position to take.

And finally—what about Zoom?

Zoom raises a whole load of other questions—as a friend has pointed out, there doesn’t seem to be any way of remunerating songwriters/composers for works that are performed or played back during a Zoom class. OK, so you’re only teaching 30 people at a time, for what could be construed as educational purposes (though ballet teaching only rarely meets the conditions necessary to be considered educational). What if your hours or numbers increase? What if you’re charging for classes? If this was the bricks-and-mortar world, you’d be paying around 1% of your turnover for the use of the music. You might be clocking up more views cumulatively on Zoom than you’d get on YouTube. I don’t know the answer, but I think the performing rights organizations (PROs) publishers and platform providers are going to have to work this out sooner or later.

Thanks to Andrew Holdsworth for the following comments on this article:

“I have a few comments on your article about cover songs on ballet albums and YouTube which I hope might be of interest to your readers. I should start by saying that I’m not a lawyer and the information and thoughts I’m sharing have been picked up over 10 years of making ballet albums and YouTube videos.

Ten years ago, the music industry was a very different beast. Most ballet class music was consumed on CD. Few people had heard of Spotify, mp3 players (and iTunes) were cumbersome, and YouTube was still figuring out where it fitted in the world of music. In those days, pianists like me who were releasing ballet albums of cover versions would fill in an MCPS form, pay our 7% of retail up front for the writers (which could mean considerably more than 7% if we didn’t sell all our CDs) and off we went.

When people started buying albums on iTunes and Amazon, our potential international audience increased, but from a rights point of view, things got more tricky, as – due to an anomaly in royalty collection in North America – these stores would pay songwriters’ royalties on sales everywhere apart from the USA. This meant that anyone releasing cover versions on iTunes would need to obtain a license from EasySongLicensing (ESL) or Harry Fox (HFA) before the albums were released. This was a pain – it involved another layer of form filling, and it was expensive. For every ballet album sold for $15, perhaps $5 or $6 would go to ESL. Some of this would go to the songwriters, but often more than half of it would go to ESL or HFA for ‘admin fees’. The only way around this was to buy hundreds of licenses at once, which would bring the cost down a bit, maybe to $4 per album. But what if you bought 500 licenses and didn’t sell 500 albums in the US? 7% was easy enough to write off if you didn’t sell all your CDs in 2000 but 30/40% was a lot more to lose 15 years later.

To complicate matters further, there was a period a few years ago where song-writing royalties on streaming platforms was a very grey area. Companies such as ELS were selling streaming licenses but they cost maybe 10 or 100 times more than the recording owner would get for the stream. For instance, ESL would charge 1p per song per stream but Spotify would only pay 0.01p per stream. I’m not sure of the exact figures but that was the gist of it. This was clearly ridiculous and unsustainable. In 2018 the Music Modernisation Act (MMA) made things much easier for ballet pianists. We wouldn’t now be responsible for paying songwriters through ESL, as writers’ royalties would be taken off at source, for every stream on every platform. Basically, the digital on demand services would have a blanket license from the publishers. Phew.

But the issue of sales of downloads in the US remains. I’ve approached a couple of aggregators asking whether they’d put albums up on every streaming platform but NOT on Apple Music and Amazon for downloads. Nobody would do it. So, every ballet album of cover songs still needs a license from ESL or HFA in advance of downloads (note downloads only) in the United States. The good news is that sales of downloads are so low these days (perhaps 5% of streaming income) that you won’t need to buy many licenses because you won’t sell many downloads, unless you’re Drake or Adele.

Moving on to your points about ballet classes on YouTube, you’re absolutely right about the Joe Wicks PE classes. George Ezra’s offer was nothing but a PR stunt. The reality is that unless you’re an entirely self-contained entity owning your own recordings and your own song-writing copyright, you’re not in a position to ‘give away’ your music rights in this way. George Ezra’s music is almost certainly not entirely owned by George Ezra, it will be split with his producers, record companies, publishers, even session musicians and managers. Interestingly, ballet pianists often do own their own recordings but unless they compose everything on their albums, or they exclusively record public domain material (anything over about a hundred years old, give or take), they’re not entitled to grant licenses to let teachers monetise their YouTube videos. Having said this, with a few exceptions (Lazy Dancer videos in the US for instance), most online ballet class videos will not generate enough income for it to be really worthwhile monetising them in the first place. You need millions of views to make a lot of money this way. But if teachers use music from their favourite ballet pianist’s album in their YouTube class, they can be fairly sure that the pianist will eventually get paid by YouTube for the use of their music in the video, even though it might only be a few hundredths of a penny if it doesn’t get many views. And the original song-writer should also get remunerated – if only by a few thousands of a cent per view.

There is of course a massive elephant in the room in this conversation – are teachers allowed to use RAD syllabus music in their online teaching? The RAD has chosen for many years not to sell any of their music digitally or to offer it on streaming services. So as far as I know, none of the RAD syllabus recordings have been registered for Content ID. This puts teachers in a difficult position for if they want to include, say, a waltz from Cinderella in their online class, there’s no way of YouTube knowing what music they’re using. So the RAD won’t get paid by YouTube for the use of the music, Prokofiev’s estate won’t get paid, the ballet teacher won’t get paid, and the only people who’ll make money from the video will be YouTube.

Despite this situation, hundreds, maybe thousands of teachers have put RAD class videos on YouTube. It’s difficult to know whether any have been filtered out or taken down but I suspect not. It’s not in YouTube’s interest to take popular videos down as they’ll lose viewers and therefore advertising revenue.

I suspect the reason that publishers haven’t instructed YouTube to remove RAD syllabus material is that it’s simply not worth their while to do so. After a difficult decade of declining CD sales, streaming has in many ways made record companies and music publishers more profitable. They don’t have to worry too much about expensive physical CD distribution any more, as most people stream most of their music most of the time. Increasingly comprehensive metadata requirements for YouTube, Spotify and the rest mean that publishers and songwriters are much more likely now to profit from the use of their music online than they were in the early days of Napster and YouTube. Digital music rights are increasingly joined up, with performing rights societies, record companies and publishers now getting the vast majority of the royalties that they’re due, even if they don’t always know where they come from. Every TV channel, every YouTube channel, every internet radio channel, every playlist will generate income for them. I expect Zoom will eventually go the same way as Facebook – they’ll negotiate a retrospective license with the record companies and performing rights societies.

For the same reason, I’ve come to the conclusion that publishers are unlikely to object to ballet pianists adjusting structures on their albums to make exercises square. Publishers have a duty to protect the moral rights of their writers, but unless ballet pianists start singing or screaming obscenities on their class albums, I don’t think publishers would object. Consider the range of cover versions now available online – from Postmodern Jukebox to Piano Guys to Macy Gray singing Metallica to dozens of dance remixes released every day, I just don’t think publishers are bothered as long as the music rights train eventually leads back to them. My rule when making my own ballet albums has always been no Lloyd Webber and no Disney, as I’ve had in mind that these organisations might be more diligent in searching out unauthorised covers – but there are plenty of other ballet pianists out there who have recorded much of this material and they don’t seem to have been locked up or poisoned so I think we’re safe. If anyone wants to make a ballet class of Trump quotes set to songs from Moana, please let me know how you get on.”

References