I had to play this yesterday at a competition, and surprisingly, it’s the first time I’ve had to do it in public. It’s vile to play. Nowadays, if I’m faced with something like this, I go back to the orchestral score to see if there’s anyway I can make the job easier for myself, or better for the audience. Click here for my new version.

Siloti’s pianistic homage versus a workable ballet reduction

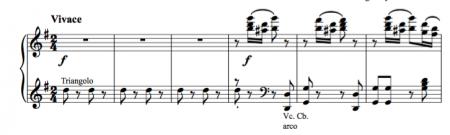

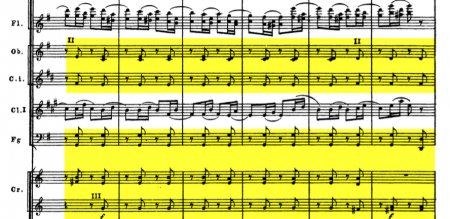

The first thing I noticed about the difference between the orchestration and Siloti’s arrangement is that while Siloti’s hovers up the top end of the piano within the span of two hands, in the orchestra, those left hand Gs are in fact octaves, an octave lower: forte bassoons, arco bass and cello. The cost of his accurate representation of detail in the flutes and clarinets is the loss of the off-beat chords played by oboes, cor anglais and three, sometimes four, horns.

Siloti’s transcription works both as a piano piece, and as a credit to what is most compositionally interesting about Tchaikovsky’s work here. But as the accompaniment to a variation, and for the dance accompanist, so help me God, it doesn’t work at all. You feel so utterly ungrounded, and so focused on the wrong things: to accompany a variation you first of all need a beat that is so strongly and safely grasped that if you need to change it, you can. Without it, it’s like trying to throw a pot with one hand; trying to steer your way out of a skid with only one hand on the wheel.

When I make arrangements like this, I do a constant accounting exercise: how much is lost if I take this out, how much gained? What’s the trade off between having a bass at the right pitch, and hearing the clarinet? I’m fairly convinced that you could get away with reducing it right down to the example on the left, and no-one would be any the wiser. Then it’s literally safe in your hands, rather than your hands being preoccupied with precarious detail, and you can use the other hand to play the bass at the right pitch, or give an impression of the horn chords; give it some weight, some “floor” in the music.

Less is more—except when it’s not

Considering how many times pianists around the world have to play the Tchaikovsky ballets in rehearsals and at vocational schools, it’s astonishing that we are still stuck with the first piano reductions, with all their inadequacies and problems and unsuitabilities. To my knowledge, my version of the Black Swan variation is the first publicly available reduction of one of the most famous solos in the repertoire. We all struggle along in our corners, doing our own ill-informed thing, assuming the score is right or the best possible, and only thinking about alternatives when problems occur.

Galina Bezuglaya, head of the Vaganova Academy music department is one of the few people to have committed anything to print about this Amongst other things, she points out that it’s mainly other pianists rather than composers (or ballet accompanists) who make arrangements, which will bring a particular perspective to the reduction; Glazunov piano reductions are difficult because he tends think orchestrally, not pianistically (on the other hand, sometimes less is less: in the Raymonda Act 3 Hungarian coda, you really want to hear a good thumping bassline in the correct (low) octave); Tchaikovsky spent half a summer simplifying Taneev’s piano reduction of The Nutcracker, because—as he said in a letter to Ippolitov-Ivanov—”Taneev’s is so difficult that it’s impossible to play” [сделал облегченное полное переложение балета, ибо С. И. Танеев настоящее сделал до того трудно, что нельзя играть]. I’ve been typesetting a lot of Nutcracker recently for a job, and every time I go to put back in something that Tchaikovsky took out of Taneev’s arrangement, I end up taking it out again when I try it out on the piano. Piotr Ilich knew what he was doing.

Tchaikovsky and Franco-Italian hypermeter once again

On a different point, what continues to flummox me (which I can do nothing about) is trying to find the harmonic, melodic shape of the opening phrase. If you place the centre of it in the wrong place, you can wrong-foot yourself badly, and be tempted to miss out a beat. I am increasingly convinced that what’s happening here is a factor of Tchaikovsky’s tendency to write in what Rothstein calls Franco-Italian hypermeter . There is a very subtle interplay here of meter and grouping that will fall apart if you try to think only of a single metrical accent. There are (at least) two, and they are in counterpoint with each other (see also this post and the one’s branching out from it). I still haven’t worked out a fail-safe way to think of this phrase, I can only get through it safely by not thinking about it. All offers of advice gratefully received.

Feedback

If you’ve suffered at the hands of the Diamond Fairy variation before, I’d be interested to know what you think of my arrangement. I deliberately didn’t post this until I’d actually done it in performance. It seemed to work for me, the best proof being that I felt able to adjust the tempo from the corner of my eye, something that I’d not been able to do with Siloti’s. Don’t take the notes in the right hand too literally: anything that approximates the harmony will do. You can steal and copy some notes from the harmony in the left hand, leave things out. I have no idea what I really played in the heat of the moment.

References

This is great! I would love to hear both versions of the variation to hear the differences! Thank you!