The curse of the operatic adage

I think I only have about three of these in my repertoire, which is why it was high time I got another. The way that some ballet teachers mark adages, you’d think the world was just full of voluptuous music that went “and one and a two and a.” I guess my worst fear is when you’re thinking of what to play, you settle on something fairly plain that will work, and then the teacher does that inclined head thing, gives you a knowing smile, and says “Something inspiring.” You have to hope they don’t add “…for a change”. This is the stuff of nightmares, because it usually wipes out what you’d decided to play (which is another reason not to decide what to play until the last minute. You never know what tempo or adjective is going to hit you in the few nanoseconds before you play the first note of the introduction).

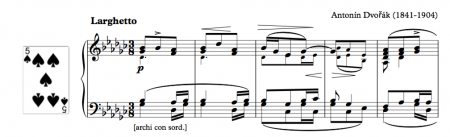

This aria from Rusalka is just about perfect. The tune really does go “one and a two and a” so there’ll be no fumbling about while the class finds the beat, and half way through, it goes all Maria Callas. I’m afraid I’ve had to do inexcusable metrical surgery on the first part, leaving out a whole 8 bar phrase in order to make it regular, but it’s hard to hear the joins unless you know the aria really well.

Playing tips

You have to have heard this before trying to translate it into piano music. The opening muted strings are hard to reproduce on a piano, and you have to do a lot of work to get the tune out on top, but If you’re lucky, you won’t have to fill it out with semiquavers, though that’s a possibility if you don’t have a very good piano or nice acoustics.

Watching this video is a rather fascinating lesson in how to play for adage well. Listen to the elastic, free, fluid vocal line in the “chorus” bit, and look how the harp accompanies it with almost metronomic rhythmic precision. It must be really precise, because in fact, the last semiquaver that you hear in the bar (part of a single group in my piano reduction) is not the harp (which is silent on the last semiquaver of the bar), but the last note of the pizzicato string figure (quaver, quaver, semiquaver semiquaver) that accompanies the harp.

Pianists tend to be “expressive” and pull the timing around in the bar, but for adage you need to choose your moments very carefully. To provide the right kind of support for a dancer who is doing the equivalent of the vocal line, you have to be as rhythmically solid as that harp and those strings, but at the same time hint at the elasticity of the vocal line. It’s something like the Chopinesque rubato where the accompaniment remains steady while the right hand floats free, but somehow conceptually different. Hard to put into words, but easy to see in this clip.

Metre issues

I’ve put this in “Spades” (Adage) because it’s quite definitely an Adage (see here for an explanation), but on the other hand, it’s about as truly triple metre as metre gets, which is common in some Czech music. Yet more proof that “three” is a big subject in music: so many ways to be triple.

Merci beaucoup pour cette généreuse contribution!