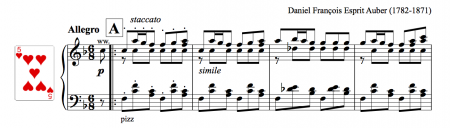

- Download music for allegro in six eight (6/8) by Auber (free pdf)

- Read more about my Year of Ballet Playing Cards

This music for allegro in six eight is what I call an “assemblé 6/8” because it’s often in assemblé exercises that teachers ask for a 6/8, or what seems like a waltz. Once the exercise starts, you realise that it’s neither a waltz, nor the kind of 6/8 that grows on trees. I call it “one of those 6/8s” (see recent post for another example), or an “assemblé 6/8” – you can also use it for some battements glissés exercises at the barre.

In music for ballet, less is often more

The longer I’ve played for ballet, the more I’ve come to appreciate pieces like this. On the surface they appear to do nothing – the bass line barely moves for the whole piece. But as a rule, taking stuff away rather than adding it seems to work well in ballet class. Structurally, too, the middle section with its upward motion and drama is all the more exciting for being set off by rather static stuff either side. What also looks like musical dullness – the same note in the bass for most of the piece, also acts like a drum, and a musical “floor” for the person doing the exercise. It’s easy to denigrate 19th century ballet music for being samey, but it works, and what the hell, Uptown Funk doesn’t suffer from having too many of the same notes in the tune either.

Well-designed music for allegro in six eight keeps you in time

This piece is a good example of music that has physical constraints in its design that prevent you from snatching a few milliseconds in the middle of the bar as you might in a waltz or jig-like rhythm. Those two semiquavers in the central beat (punctuated by horns in the orchestration) keep this in a genuine three, and make you hold your tempo. I borrowed the idea of physical constraints as a design feature from Donald Norman’s The Design of Everyday Things .

The value of physical constraints is that they rely on properties of the physical world for their operation; no special training is necessary. With the proper use of physical constraints there should be only a limited number of possible actions – or, at least, desired actions can be made obvious, usually by being especially salient. (Norman, 1989, p. 84)

An example of this in everday life would be a door that had a push-plate on one side, and a handle on the other. You simply couldn’t pull the door on the push side by accident because there’s nothing to grab, and you would naturally go to pull the door on the pull-side. In this music, those semiquavers are the physical constraints, they prevent you from squeezing the tempo in the middle of the bar. The same principle works like a dream when you use polka-mazurka types for a pirouette – it’s almost impossible to get out of time.

About the arrangement

Despite it’s simplicity, this piece was difficult to reduce for piano, and I’m still not happy with it, after several revisions. It’s hard to capture the bouncy lightness of the orchestration on a piano with only two hands, so this would probably make a nice duet. In three places, I’ve missed out one beat, in order to drag the piece into a meter that works for class. The start of it comes from Act 1 (should start automatically start in the right place when you click, but if not, drag the slider to 6:11)

The A minor section comes from Act 5 (starts at 16:17, again, should start there automatically on click, but drag to the right time if not). Altogether, this week’s score has four variants of 6/8 for allegro, one of which will probably work for the exercise. It’s handy to have a piece that keeps changing rhythmic emphasis like this, because then you can see which particular variant works. You’ll notice that the final section also removes the constraint that I wrote about in the F major section – which will be either a good or a bad thing, depending on the exercise.

The Auber in the Tchaikovsky

I can’t say I was much of an Auber fan before this week, but the more I listen, the more I like it. There are some really bizarre, tender and wonderful moments of orchestration. I also began to realise how much Tchaikovsky’s dance music resembles Auber at times (the Tchaikovsky pas de deux female variation could have been written by him, in places, and there’s a bit that sounds straight out of a march in Swan Lake.

There’s also a strong resemblance between this last A minor section from Act I, and Tchaikovsky’s “August” (Harvest song) from The Seasons which is used in the pas de trois after the duel in Onegin. There seems to be a worldwide competition to play this as fast as possible, until the rhythm just blurs into rabid prattle of notes, but I do rather like this orchestration, which makes the piece sound a lot better than it is:

Bibliography