- Download Verdi – Ballet music to Jersusalem (Act 3, 16: No 2, Pas de deux) (free piano score pdf)

- Read more about my Year of Ballet Playing Cards

There’s a kind of allegro that’s in 6/8 that needs music like this. I don’t really know what to call it, except “a six eight allegro.” The canonical example for me is “Sempre libera” from La Traviata (below):

The trouble is that there’s only about 16 useful bars of that aria, and for this kind of exercise that comes forward in multiple groups, you need at least a hundred. Most of the things I know that fit the bill are equally short, or turn out to have too many notes to keep up the necessary speed without wilting. Also, the exercise usually needs lift and movement in particular places, so I usually end up improvising – until I found this piece from Jerusalem.

Tip: Useful is not always interesting, and interesting is not always useful

I was going to skip this in favour of something that looks more interesting on paper, but when I came to play it, it felt and sounded better as performed music than it does on the page, and it’s also very handy because it goes on for ages. Even though I can hear a score in my head by reading it, there is often – as with this piece – a chasm between what it feels and sounds like as a physical experience, and what it looks like on paper. I’m certainly influenced by just how useful this is, so maybe a normal pianist (rather than a ballet pianist) wouldn’t feel that way.

What I love about this piece, the more I hear it and play it, is its constantly changing rhythmic shape. I wouldn’t have noticed this so much, or had the words to talk about it, had it not been for two instances recently where I was supposed to be teaching pianists, and learned something myself.

The first occasion was in Ljublana, (photo gallery here) leading a weekend seminar for ballet teachers and pianists at the Conservatoire for Music and Ballet. A question came up about battements tendus with the accent in or out: how much does that affect the music that you should play? I wasn’t giving answers, it was a discussion between teachers and pianists. After nearly 30 years of playing for ballet, I noticed something for the first time: teachers, when they want to stress the accent in, appear to give more “accent” to the out preceding it. That figures logically, because if you want to chop a log harder, you lift it higher before it falls, and you have to show that the leg is out before it comes in on one. But it really messes with your metrical head, because you hear “accent in” as a verbal instruction, then you hear “AND a 1″ as a musical cue. Also, “accent in” doesn’t (I think) mean accent in the sense of chopping logs, but of where the close is in relation to the musical metre.

Franco-Italian hypermeter in the ballet class: try it, you’ll like it (and so will they)

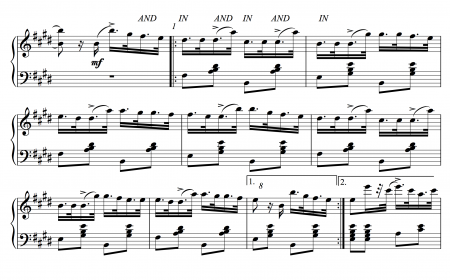

So maybe this is a case for pieces that exhibit what Rothstein explains as “Franco Italian hypermeter” (see previous post) I tested the theory by playing this piece (playing card 46) which has more than half a bar anacrusis (which is one of the requirements), and asked teacher Tom Linecar-Boulton during a London Amateur Ballet class to see if it did the trick. It seems to, and it illustrates a fascinating thing about the incommensurability (in my view, at least) of musical accent with ballet accents. There’s a lightness and accentuation about this which has a very different kind of body to it than non-ballet music, and “anacrusis” in music has too many implications about downbeat that may not work for dance. What it has is a long “and,” not a heavy one, and the one has an accent which is not to do with volume or weight, but – I don’t know how to describe it – where it is. It’s like saying “I’m going to put this here, and that there,” without shouting about it.

Franco-Italian hypermeter in a six eight allegro

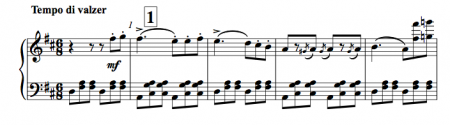

The second occasion was yesterday, when I was talking to some music students who were going to have a go at playing for ballet classes. They were asking if it’s acceptable to have a stock of chord sequences that you improvise over. I said yes it was, and that it’s surprising how much a simple repeated sequence can be masked by the detail that you hang over it. I took this Verdi piece as an example. It’s in 6/8, but as Danuta Mirka would say, the “composed meter” varies – that is, the first two bars are indeed in duple with triple subdivision, but then the next bars, with the little grace notes, and the emphasis on each beat, are effectively in 3/8. As the piece goes on (I’ve sewn two together and done a bit of reworking to try to make enough for several groups), there are many variations on the rhythm of the phrase (with an anacrusis, or on the beat, with a half-bar anacrusis, or a short one) even though the basic duple structure is maintained. My favourite is this one:

“A bit lighter please” — try meter, not dynamics

This to me solves a conundrum with a certain kind of jump that jumps before the 1, yet mustn’t be heavy. When a teacher I played for recently kept saying “a bit lighter” I thought he meant just “quicker” but I think he really did mean lighter – but in the sense of not thumping either downbeats or upbeats, but maintaining a kind of tension between the two, as in this wonderful example.

You’d have to pick your moment to play this – if the dancers need the music to tell them what to do on every step, then avoid it – but if they know what they’re doing, the subtle shifts of grouping over the phrase bring all kinds of lightness and accent to it, in a way which is definitely Franco-Italian, and not German: what you have to avoid is obeying the (Germanic) rule that every downbeat has to have an accent. Think about Italian or French poetry, with its end-accented lines, and swoop over the bar lines, resisting the accents until the final bar.

I can’t find a recording of this that is at a tempo which I think would work for class, so I’ve done a very rough one here – my apologies for the botched job, but I’m sight reading, and the piece has only just come out of my musical oven. Teachers, I’d love to know what you think about this, and whether I can give a name to this (is it particularly good for a certain kind of jump?).

If you can’t play this, or want to download it, right-click (or command click on a Mac) this link

The point of posting stuff like this is not to bring back Verdi’s Jerusalem because it’s the best thing for allegro, but to offer models for either improvising or finding other repertoire, and the changes of accent, metre, phrasing, rhythm, grouping and so on in this offers all kinds of ideas.