Maybe I’ve just led a sheltered ballet life, but after 30+ years of playing for more rehearsals and casts of the white swan pas de deux from Swan Lake Act II than I can remember, I was astounded the other day to discover that there was a bit of the score that I didn’t know—never heard it, never seen it. For a recording project, someone asked me for a piano version of Nureyev’s solo for Siegfried from Act II. I hope you’re all going what act 2 solo? with me.

So here it is:

Le lac des cygnes – act 2 Siegfried variation from seminkova on Vimeo.

I almost despaired to the point of emailing Lars Payne, orchestral librarian at ENB who knows everything [see earlier post] there is to know about ballet music, particularly Swan Lake, but I’ll admit it, I was too proud to confess that I didn’t know what it was. So I started searching, and found something on the Nureyev Foundation website that said “Nureyev restores the prince’s variation which used to be habitually cut after the dance of the big swans.” Again, I thought “which variation?!” I had already looked through the 1877 version of the score at least twice, trying to find it, and through the 1895 Langer version, to see if was something that had been added posthumously. As I listened, I began to doubt myself: is this Tchaikovsky at all? Since I had already promised to record it, I began to dread that it was (as turned out to be the case in another Nureyev restaging) John Lanchbery had quietly faked a Tchaikovsky-like solo to save the day.

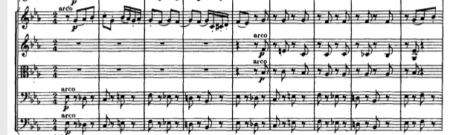

I had another look at the Kashkin score—which by the way, I’ve used for years—and sure enough, there at the end of the pas de deux (not after the dance of the big swans, actually) is the so-called “prince’s variation,” which is more like a coda for the pas de deux couple. In fact, my experience was what made me miss it in the first place: I was so used to the conventional ending to the pas de deux, that I wasn’t expecting to see anything novel there—so I didn’t. You can find it yourself in the Kashkin score on IMSLP, but in case you miss it and to save time, here are the relevant pages in a two page file.

It’s in nicely rounded 8-bar phrases except for the last phrase, which is 6 bars—though you could cut it or extend it easily. In typical Tchaikovsky fashion, there’s a kind of trompe l’oreille effect, whereby the first motif sounds as if it’s an anacrusis, but it is isn’t—it keeps chasing its own tail like a Möbius strip.

Eventually, I remembered that I had seen it once before, though without registering any of the notes. I was playing for the Ballet Masterclasses in Prague, where we were going to White Swan in the pas de deux class. I said very casually, oh yes, it’s fine, the score’s on IMSLP, no need to worry. With about 5 minutes to go before the class, I printed it off, and then to my horror, noticed that the ending I was expecting. Fortunately, we did have a score of the right version.

Yes, it’s on some orchestral recordings. Strange to think it was like that originally

thank you, jonathan–that music is on the michael tilson thomas lso recording and he takes it quite fast, and i always thought it was an orchestral coda-to-the coda, sort of change-of-blocking music–very interesting to see it slowed to a full out male variation

As usual I am very late to the party! The Nureyev Foundation’s Swan Lake page has errors regarding historical information. There was never a male variation in the 2nd tableau “lakeside scene” of Swan Lake. In Tchaikovsky’s original score of 1877, the famous White Swan Duet ended with a brief, faster allegro movement (the music Nureyev used for this solo). For the revival of 1895, Riccardo Drigo cut the allegro ending and composed the familiar ending most of us now know from live performances (Drigo’s new ending begins at bar 94). Interestingly, in his otherwise incredible book “Tchaikovsky’s Ballets”, Roland John Wiley makes the absurd claim that Tchaikovsky’s original composition of the White Swan Duet with it’s adagio that ends with a fast allegro movement was meant to represent what he calls “Siegfried’s inconsistency”! What nonsense. I have no doubt that in 1876 Tchaikovsky was told by the balletmaster Julius Reisenger to end the adagio in this way – its the way a “Grand adage” almost always ended for most of the 19th century, particularly during ballet’s Romantic era: with a brief, faster “allegro” movement. By the end of the 19th century this fell out of fashion. Like Tchaikovsky in 1876, Drigo in 1895 was also doing as he was told… Petipa certainly told the Maestro to make all the changes to the score, including the ending of the White Swan Duet…but I digress!

Nureyev resurrected the original allegro ending of the White Swan Duet to accompany a variation for Siegfried in the 2nd tableau. As usual, his choreography is awful – a pretentious mixture of an Eric Bruhn styled barre and center and modern dance movements. But I do think it’s a good idea to utilize this music to serve as a variation for Siegfried!

And as usual, you correct the historical record(s) yet again. I’m ever grateful for your vast knowledge and unsurpassedly helpful insights.