What a difference an e makes: the difference between a grand waltz and a grande valse

Ballet teachers often ask for a “grande valse” or a “grande waltz” or a “big waltz” for grand allegro, probably as a result of someone telling them to do so on a teacher training course, but to be honest, it’s a misleading and much misunderstood term. It’s clear from the way that many teachers make a kind of Popeye-flexing-his-biceps gesture as they say “grande valse” that by grande they mean something with oomph, or butch, or—to use a phrase I haven’t heard for years—to give it some welly.

But the grande in grande valse in compositional terms refers to the scale and nature of the work (i.e. long and discursive) rather than its dynamics or capacity to be used for big jumps. And there’s the problem, because when composers write large-scale works, they usually introduce contrast, interest, variation, symphonic-style development, the unexpected, including changes of speed, and the playful expansion of melodic material. For that reason, many of the pieces in the concert repertoire called grande valse won’t be that useful for ballet class, given that what is needed is a succession of 16-count phrases of similar dynamics for each group of dancers as they come across the room. Composers of grandes valses don’t last long before the temptation kicks in to try some canonic imitation or rhythmic dissonance over a pedal point. If you’re trying to do grand allegro, or play for it, this is often more of an annoyance than an interesting feature. A notable exception is Chopin’s grande valse op. 18 No. 1, which has a lot of usable sections in it—but on the other hand, it’s not very “grande” in terms of tempo and oomph.

Tcherepnin’s Grande valse: the best bits

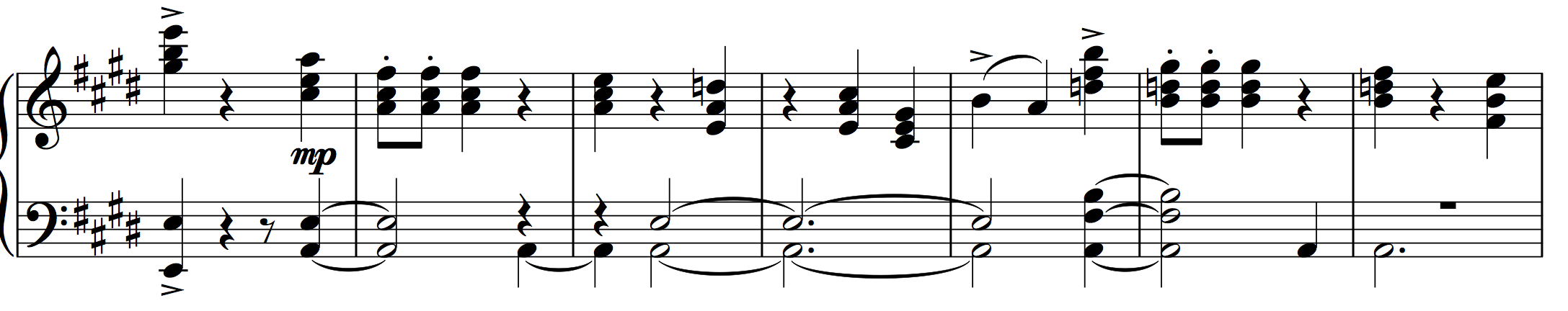

Tcherepnin is unfortunately no exception to the general rule (incidentally, it should really be Cherepnin—the ‘T’ comes from French transliteration, where the T is needed to make the “ch” sound, otherwise it would be pronounced “Sherepnin”; Chaikovsky, a.k.a. Tchaikovsky is another example). No sooner has he stated his big tune, than he begins to take it apart, like a dog pulling at a lead while you’re trying to head straight through the park. Depending on the exercise, there might be times when this can work, and in principle, If you’re going to have 10 minutes of grand allegro, much nicer to be able to play stuff that develops and changes than keep repeating yourself. For that reason, I originally intended to transcribe the whole waltz: it’s wonderful. However, I had to keep cutting and cutting until there were only two pages left. In grand allegro, you can’t suddenly drop from fortissimo voluptuousness into the coy experiment in the example below. It’s an example of what Christopher Hampson once called being “musical” in a pejorative sense (see earlier post on “Being too musical“). The grande valse concert repertoire is littered with them, which is fine if you’re listening rather than dancing.

However, the first couple of pages of this is great for a certain kind of travelling (rather than jumpy) grand allegro, and it’s wonderfully dramatic, wistful and film-scoreish in a similar vein to Geoffrey Toye’s 1934 Haunted Ballroom waltz .

Listen to Tcherepnin’s Grande Valse from Le Pavillon d’Armide

Many of the Youtube classical music links I post eventually disappear for copyright reasons, so listen while you can.