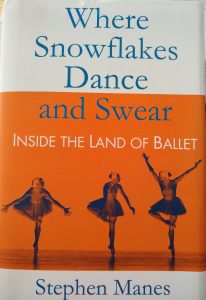

I bought Where Snowflakes Dance and Swear when it first came out in 2011: I didn’t particularly want to read it (because I spend enough time in this world at work) but I couldn’t ignore it as a kind of ethnography of the ballet world that I was writing about. It was a good decision: unlike so many other authors of backstage views of the ballet world, Stephen Manes actually talks about music—the problems, what people play, the problems of hiring and marking up orchestral parts, how much it costs, and so on.

I bought Where Snowflakes Dance and Swear when it first came out in 2011: I didn’t particularly want to read it (because I spend enough time in this world at work) but I couldn’t ignore it as a kind of ethnography of the ballet world that I was writing about. It was a good decision: unlike so many other authors of backstage views of the ballet world, Stephen Manes actually talks about music—the problems, what people play, the problems of hiring and marking up orchestral parts, how much it costs, and so on.

For anyone who has ever had a problem with music publishers, copyright and licensing in the ballet world, pages 252-258 will probably be one of the first times you’ve seen your experience represented in a published book, with the exception of Matthew Naughtin’s Ballet Music: A Handbook, which tells the story (and gives information) from the music librarian’s perspective. Even he, though, doesn’t get into the kind of gory embarrassing detail that Manes does, where a company has to do things that are on the grey, fuzzy margins of legal, in order to get by. Everything in these pages I had experienced myself, and was delighted and surprised to see that my troubles had been shared by others. You think you’re mad, criminal and incompetent until you realize it’s the craziness of music publishing that is the problem.

I can’t think of another book or article that contains so much about everyday musical practice in the ballet world: what pianists play for class; the decision to use CD or piano for rehearsal; the embarrassing moment when you do a new work, and find that there’s no rehearsal score, so the company pianist has to do one. It’s just a shame that you have to trawl through the book looking for the references—the indexing could be improved so that it’s easier to find topics, rather than very granular references to particular people or ballets, but at least the references are in there somewhere: ethnographies of ballet often say little more than ‘classical music plays in the background’ and leave it at that, so this is a welcome change.

Ballet pianists and company class

The author (see comment below) has reminded me of one of the biggest sections on the work of ballet pianists, on page 697-703, with detailed explanations from two company pianists, and their route into the profession. One ended up playing for the company “because they hated the class pianist” (p. 698), another started out when he was left to sink or swim in a class in Moscow— “. . .there’s something about someone foreign yelling at you, screaming at you. . .” (p.700). Quite. We’ve all been there. But the balance in Manes’ writing is everything: despite the awfulness, there are compensations, and reasons why ballet pianists end up loving their job and staying in it. A lot of so-called “behind the scenes” writing on ballet musicians is nothing of the sort, because it’s commissioned and written under the auspices of the ballet companies themselves.

Repertoire

Dotted around the book (and this is what prompted this post) are little references to music that to my mind, make a huge difference, not just to the evocation of the scenes that the author is describing, but to our knowledge of what music in the ballet world is like generally. The book may be specific to a time and place, but musically, it sounds very familiar: “A medley of ‘Stairway to Paradise,’ ‘Bidin’ my Time,’ and ‘Nice Work if You Can Get it’ played with strong emphasis on the beat accompanies a combination that involves what Otto calls ‘many’ turns.” (p. 44). Stretches are done to a Dvořák Slavonic Dance, and sit-ups to Carmen (p. 119); “Flashy jumps and big turns to Beethoven, Bach, “Be a Clown,” and “Meet Me in St. Louis” begin to lighten the mood of the room. (p. 505). In a description of a rehearsal, Manes mentions that “The Merry Widow Waltz” wafts in from an adjacent classroom (p.173), prompting a momentary digression in the rehearsal to remember fondly the time the company did Ronnie Hynd’s ballet The Merry Widow.” It’s a lovely detail—it’s exactly the kind of thing that happens in rehearsal. In writing about ballet, there is usually so much emphasis on the hyperfocus and determination of dancers as elite athletes, that these little overhearings and spillages of music and memory usually go unmentioned.

I’m always delighted when readers discover specific aspects of the book that otherwise have gone unmentioned. Thanks for the astute comments. And for your readers, I’d also call out pages 697-703, which specifically address ballet pianists’ travails, .

Thank you for reminding me about the section on playing for class on 697-703. This is one of the sections I’d stickered in my copy of the book, but had forgotten about how much detail there was there. I’m going to develop this post a bit and include more of the references to music. I was just so thrilled to see the stuff about the crazy practice of hiring music, when you have a copy yourself. I once said to a publisher “I’m not going to use it, so maybe you could save yourself the time and cost of shipping it from Germany, and us sending it back? We’re still going to pay you.” It was as if I hadn’t spoken, and that’s when I understood that going through this rigmarole is one of the unspoken rules.

Thanks for the extra bonus material! I’m delighted to see someone notice that this book offers a much broader focus than just the dancers and choreographers. In addition to covering the music, I’m very proud of approaching essential aspects of ballet such as lighting design, stagecraft, and financial management that have rarely drawn mention elsewhere.

As a board member of the Authors Guild, America’s oldest organization of writers, I’ve always been obsessed with the way book contracts rule authors’ lives. Contracts in the music world, I discovered, are even more byzantine.

A final pro tip re music: If you look up the entries for “Stewart Kershaw” in the book, you’ll run across most of the scenes involving the ballet orchestra and its conductor. I found the interplay between choreographers and musicians consistently fascinating.

I enjoyed the broad focus of the book, particularly the financial stuff, because what seem superficially to be “artistic” decisions are often in fact rooted in money or contracts; it’s rare to see the discussions laid out so transparently. I had noticed the Kershaw sections, and I love the detail you go into, and the amount of reported discussion, which is quite unusual. As I’ve written in the blog post, it’s the detail about what people play for class that I appreciate most, because it’s so often passed over when people write about it, either because it’s regarded as not important, or they don’t know what they’re listening to, or they don’t ask. In documentary films, the music is increasingly overdubbed with something else to avoid copyright and licensing issues, or TV companies leave out those sections altogether for the same reason, or pianists change what they play to avoid the issue. As a result, it’s only this kind of reporting that gives an accurate picture.