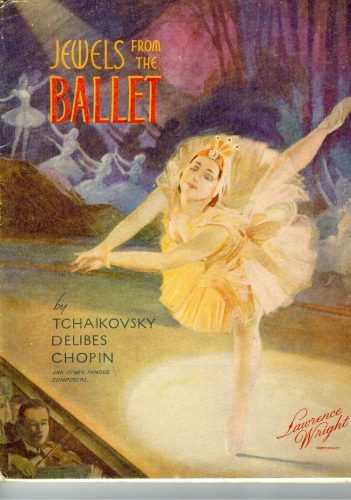

I’ve seen this book so many times in my life, either as the piano version, or the one for violin and piano, that I have come to instantly disregard it. Oh yes, that book, with all those tunes that I know backwards, standing on my head. To be perfectly honest, I’ve been a bit snobbish about it, most likely because, published in 1946, it looks like the kind of book that was already long out of date and out of fashion when I was a child in the 1960s, and spoke to me—whenever I saw it in second-hand book shops or on the shelves of ballet schools—of a thankfully bygone era. I mean, who nowadays would use a phrase like jewels of the ballet?

And that oddly composed picture—it’s so full of quaint sentimentality, compared to those faceless sweaty Athena-style prints of the 1980s: perfectly-crossed fifths in legwarmers, or the close-up of the pointe-shoe battered toes of a ballerina. If I’m even more honest, there’s something about being classically trained that makes you think that serious music shouldn’t have pictures on the cover, unless they are black and white engravings from so far in the past that they are historically informative. It shouts “commercial!” at you, when you want to believe that the people who publish the music you play are doing it for scholarly, dignified reasons. Such thoughts are so deeply embedded and habitual, that it’s only when I came to pick this anthology up and look at it more carefully that I recognised my own absurd prejudices.

Pauline Grant and On with the Show

I took it off the shelves because I wanted an example of a certain kind of anthology. This’ll do, I thought. I turned the cover, expecting to find the contents page, but to my astonishment, found this full-page picture of a tableau called “Wedgwood Group,” choreographed by Pauline Grant for “On with the Show” on Blackpool North Pier. And then the trip down the historical rabbit-hole started. Even though I was supposed to be writing about something quite different, I couldn’t get this picture, and what it symbolized and portrayed, out of my mind. I instantly thought of what VIrginia Taylor says in her thesis about the contrast between dance in the working theatre, and the companies that we know most about such as the Royal Ballet or English National Ballet, and a phrase used by one of my school friends about his sister, a ballet dancer (albeit not of this period): she did all the summer shows.

“End of the pier show” is used pejoratively, but this was by no means vaudeville: Pauline Grant choreographed the Tchaikovsky Serenade for Strings (the same piece that Balanchine used for Serenade) for this number in On with the Show on Blackpool North Pier. There are a few more pictures after this one, of Pauline Grant, Mona Inglesby, and, with no great fanfare or top billing, Margot Fonteyn. I began to do my homework on Lawrence Wright, and discovered via this fascinating page on him from the Blackpool Museum, that he’d produced the long-running On with the show, and so now the connection between Pauline Grant, Jewels of the Ballet and him began to make sense: he was publishing music that had been heard in ballets in his shows.

The more I researched, the more interesting it got. I had heard the name Mona Inglesby, but in somewhat disparaging terms, which I now realise is rather shocking, but also understandable: despite her enormous achievements and massive popularity, she has been all but wiped from ballet history. Her completely self-financing company International Ballet had 60 dancers and an orchestra while the Sadlers Wells were playing safe with Constant Lambert and Hilda Gaunt on two pianos playing arrangements. The Musicians Union thanked Inglesby for having kept so many musicians in work during the war.

English ballet history: Ismene Brown’s Blackout Ballet

I then found that Ismene Brown had had a similar shock of recognition when she was researching for an article about the Kirov’s recentish reconstruction of the Sergeyev Sleeping Beauty. Mona Inglesby not only had Sergeyev to teach her company the original choreography from the notations, but after Sergeyev died, she sold the scores to Harvard (where they are now), who at the time seemed to be the only people who recognised what a legacy this was. Ismene Brown’s 30 minute BBC radio programme about this, Blackout Ballet is available here—scroll down to the bottom of the page for the audio (but read the page, it’s fascinating and wonderful). A transcript of Blackout Ballet is available here, with some pictures as well.

English ballet history: Karen Eliot’s Albion’s Dance

After that, it was only a matter of time before I found Karen Eliots’ Albion’s Dance which documents this period in detail, painting a remarkable picture of ballet in wartime England that I simply had no idea about, companies that had come and gone, sometimes with enormous success, and certainly bringing ballet to audiences in a way that seems unimaginable now. Among others, Eliot quotes some lovely stories from Joy Camden’s autobiography, and it makes me sad to think that I had no idea who I had been talking to when I played for her RAD exam session for a week in Newcastle back in 1986, and that it’s taken me 33 years to find out, mainly because English ballet history has been so skewed by the big, arts council funded names.

The biggest surprise of all, which I am still pondering, is that all this music which I knew as a child from albums like this, had perhaps been made famous not by the big-name companies, but by these passionate, hard-working war-time ones. If it hadn’t been for Lawrence Wright and Pauline Grant and Blackpool Pier, would I ever have been sitting at a piano in the 1960s playing selections from Coppélia and other pieces in this album? Would Les Sylphides and Coppélia, La Source, and The Nutcracker been regarded as “classics” had it not been for Mona Inglesby and her touring?

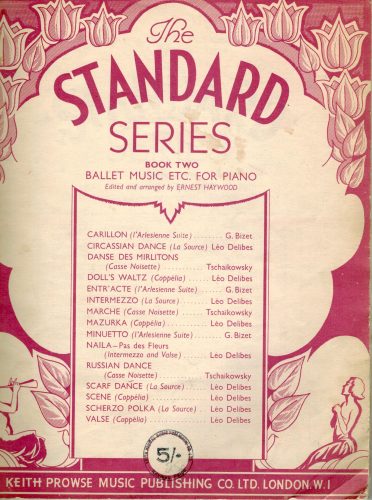

And just as an aside, here’s the book which in a sense gave me a career. The Keith Prowse “Standard Series” Book Two, Ballet Music etc. for piano arr. by Ernest Haywood. I had listened to the LP we had of Coppélia countless times, and loved it as a child, and learned to play the mazurka from this book, and did so over and over again. I was so astonished to find one day that I could make a living out of having so much fun.

Hi Jonathan, Thanks for this post. Joy Camden was my favourite teacher at Bush Davies! I didn’t really know what or where she had danced, but her exercises for ballet class were wonderful and it was clear to me that she had a very strong professional background. She also taught wonderful character dance classes!

Her biography is absolutely extraordinary: taught by Legat and Preobrajenska as a child, Ballets Russes when she was fifteen or sixteen, marooned in London because of outbreak of WW2, so joined Rambert, then 50 weeks a year (!!!!) touring with Anglo Polish Ballet where she probably learned a lot of the character she taught you (she got in easily because she’d been taught mazurka aged eight!), The Red Shoes, and loads more. You can read a lot of her autiobiography, Survival in the Dance World in Google Books preview. How I wish I’d known all this when I was working with her!