I said it had been a week for finding things: well, it’s not over yet., apparently.

The Bugatti Step

As this will be a longish ramble about finding music, I’ll cut to the chase. The Bugatti Step by Jaroslav Ježek is a fantastic piece of piano music that you could use for class, and the sheet music is available online. I’m not usually guarded about sharing ideas for class music, but in this case I have to confess it’s taken me weeks to do so, because I love it so much, I don’t actually want my colleagues to have it in their repertoire as well. But I can’t help it. It’s too good not to share.

How I discovered Ježek and the Bugatti Step

What prompted me to finally share the score was that the route to finding it (and other music by Ježek) has been so delightful and interesting. Not long after I vacated Facebook and Twitter a few weeks ago, I was listening to the radio in the car, and heard Barry Humphries talking about his forthcoming show at the Barbican, a presentation of music from the Weimar period, including some of my favourite cabaret songs and composers. As I love the music of this period, I thought I can’t possibly miss it. I checked the dates. Then, because I wasn’t on Facebook anymore, I wrote an old-fashioned email to someone who I thought would appreciate this as much as me, but who is probably the busiest person I know, and lives hundreds of miles away. I don’t suppose by any chance you’re in London when this is on, and free? As it turned out, he was, and so we went, and it was wonderful.

Barry Humphries presents this collection of music as if you’re having a pleasant after dinner chat in his sitting room (or, if you’ve ever been there, the Kleine Philharmonie bar in Berlin, which in turn looks like the set of Cabaret). The story he tells is wonderful: as a young man, he discovered this music in second-hand shops in Melbourne, remnants of the possessions of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, who had clearly loved the music enough to bring it with them. He fell in love with it, and has ever since nurtured a fascination with it, leading eventually to this show.

One of the first pieces in the programme was Bugatti Step, played as a piano solo. I couldn’t help thinking, this is wonderful music in itself, but it would also be great for class, so I made a mental note to check it out afterwards. The composer, Jaroslav Ježek, (known as “the Czech Gershwin”) as so many others, was forced in the late 1930s to flee the Nazi occupation of Czechoslavakia and go to New York, having until then been a huge contributor to the Czech music and theatre scene.

What comes across as Humphries introduces the music, is a sense of loving and cherishing these pieces, of giving them the value and the hearing they deserve; a will for them and their composers not to be forgotten. It’s infectious, but It’s something more than enthusiasm; there’s a warmth and intelligent sensitivity about Humphries’ advocacy of this music that sometimes helps you hear it almost too closely for comfort; you hear with the ears of those who wrote it and heard it at the time. It’s hard not to draw parallels between the politics of then and now.

Rendezvous with Ježek in Prague

So now fast-forward a little (I went to the concert on 23rd July, and it’s now 10th August), and I see an former Czech colleague of mine at the studios in Prague—she used to play for class when the ballet masterclasses in Prague that I’m at now first began. Years ago, she had told me where I could find a second-hand music shop in the city. I asked her it was still there. She checked on her computer; she wasn’t sure, but there’s this bookshop in Wenceslas Square No. 42 that has a new and second-hand music department. By chance, I was walking there in the afternoon, so popped in.

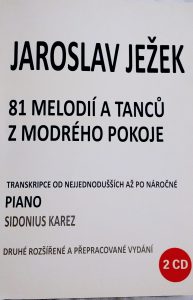

And blow me down, one of first things I see on the shelves is a book of 81 songs and dances by Ježek, arranged for piano byu Sidonius Karez. (81 melodií a tanců z modrého pokoje). I had to buy it, even if I wasn’t sure what I was going to do with it. I’m glad I did. It’s a wonderful book, lovingly and carefully put together, with interesting panels of information about Ježek and photographs of him and fellow musicians and performers from the Liberated Theatre in Prague. I can just about work out what it all means, with a bit of help from Google Translate, and my background as a Slavic languages graduate. I start to search for the original 78rpm recordings on YouTube. The music is just wonderful.

Musical journeys

I’m telling the story because it’s not the first time that my route to finding music has been face to face, material, hand to hand. Meeting people, going to bookshops, being present somewhere. If I hadn’t been to that concert at the Barbican, I might never have heard of Ježek, or had the chance to be thrilled by his music. Barry Humphries found the music in a second-hand shop where it had come from Europe in the 1930s. And now, I’m finding more of it, actually in Prague, in a bookshop, because I bumped into my colleague and she recommended that bookshop. I would not have known what I was looking at, had it not been for someone bringing that music to Melbourne in a suitcase, and Barry Humphries looking after it, and years later, presenting it at the Barbican. If I hadn’t got off Facebook and made the effort to make arrangements to see a friend in real life, I wouldn’t be writing this now.

There are other ways to find music, of course, and YouTube is great for researching what has already triggered your interest. But for me, at least, the music you discover like this, passed from hand to hand, music that you can touch, or music that you hear in the physical presence of others, is somehow always more precious. Barry Humphries tells a story in the show about how his mother didn’t like library books “because you didn’t know where they had been.” For him, that was precisely what he liked about them, and that was the appeal of the music he had found in the second-hand shops that led eventually to this concert.