This is the fifth or sixth post I’ve written on mirlitons in relation to Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker, having tried for as long as I’ve been playing for rehearsals of the piece to make sense of the title. What bothers me is that it’s all very well to know that mirlitons are some kind of kazoo/flute/reed pipe, but why would Tchaikovsky call something “reed pipes” or “shepherdesses” in a set of divertissements that otherwise are names of sweets? And beyond that question lies another—if it’s so hard for us in the 21st century to make sense of what a mirliton is now, what was it to Tchaikovsky and his audiences in the early 1890s?

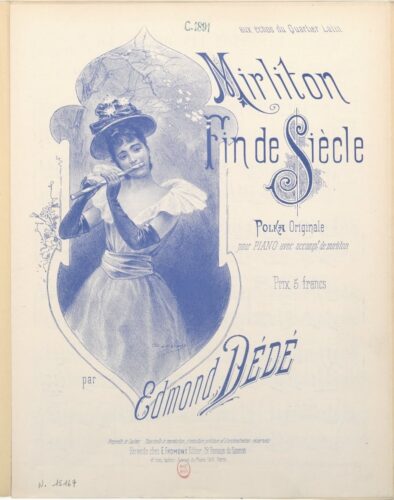

A piece of Parisian sheet music from 1891 (see the original here on IMSLP) provides the best clue I’ve found so far. It’s a polka with “mirliton accompaniment” by Edmond Dédé. Other bits of information that I’ve found since the last time I posted are also interesting—that an 18th century composer, Michel Corrette (1707–1795) wrote a “Concerto Comique” called “Le Mirliton” which is also, incidentally, scored for three flutes. The Andante middle movement of this features the song “Vive Henri IV” which provides the theme of the apotheosis in Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty.

“Mirliton” is also a rather bizarre bit of French military uniform (a replica of which you can buy here, if that takes your fancy), and apparently also the word for the countdown to an exit sliproad you see on motorways in the UK, or a form of signal on SNCF railways (which you can buy for your model railway here). All of which provides plenty of reasons to wear stripy costumes.